In the late 1960s, the BBC’s Saturday line-up fell under the auspices of head of light entertainment, Bill Cotton – and it was shaping up to be a formidable operation. Cotton, the son of the famous band leader of the same name, began his career at the BBC in 1956 and developed a reputation as light entertainment producer extraordinaire. The launch of BBC2 in 1964 allowed the corporation to justifiably jettison many of its less popular programmes to the minority channel, and created an invaluable test bed for new acts and ideas. In acquisitive mood, Cotton poached disc jockey Simon Dee from Southern Television in 1967and brought him to Saturday evenings. This was followed by what would turn out to be one of the most significant television acquisitions of the decade.

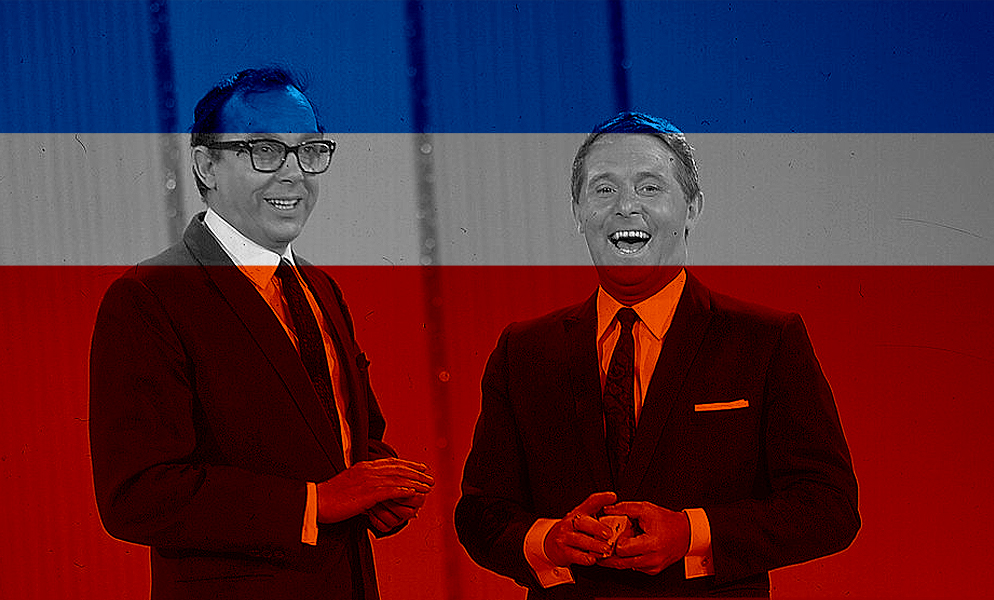

Describing their deal with ATV as not “altogether satisfactory for us,” legendary comedy double act Morecambe and Wise were tempted over to the BBC thanks to the initiative of their agent, Michael Grade. “Bill [Cotton] couldn’t believe his luck,” Grade remembered. “Once he realised I was serious, he gave them a series on BBC2 in colour and launched them on a dazzling television career.” Grade had been privy to the Eric and Ernie’s long-standing dissatisfaction. Their shows were smash hits in North America; they had recorded an album (An Evening with Ernie Wise at Eric Morecambe’s Place) and had broken box office records with their summer show in Great Yarmouth.

Yet desperate to embrace colour television, their contract renegotiations with ATV boss (and Michael Grade’s uncle) Lew Grade had ground to a standstill. “You’ll have colour when I say you have colour,” was all Grade senior had to say on the matter. “I got into a taxi,” recalls Cotton, “and went straight round to Michael’s office and offered a three-year contract based on a figure that was over the top for the first year but, if my judgement about their drawing power was sound, would prove to be a bargain by their third.” This deal was to be pivotal in the establishment of the BBC’s modern light entertainment identity, yet just three months after starting the record of their first BBC show, on Sunday 3 November 1968 to be exact, Eric Morecambe felt a twinge.

“It was in the arm,” he recalled, “rather like a tennis elbow or a bit of rheumatism. Whenever, I pressed that arm, the right, in the funny bone I would get a shooting pain.” Aware of his own hypochondriac tendencies, Morecambe ignored the persistent pain and he and Ernie Wise continued with their run of midnight performances at the Variety Club in Batley, West Yorkshire. However, by the Thursday morning he was feeling worse. On his way home from that night’s show, Morecambe finally conceded there was something seriously wrong. Enlisting the help of a 23-year old tyre fitter named Walter Butterworth, Eric was able to admit himself to the casualty unit of Leeds Royal Infirmary and was diagnosed as having suffered from a major heart attack. While the incident gave Morecambe another story upon which to dine out (Butterworth asked Morecambe for an autograph – “before you go”), for a time, the future of his performing career was seriously in doubt.

When it did recommence, it was initially on BBC2. The decision to unite Morecambe and Wise with a new writer, Eddie Braben, made all concerned nervous. Braben’s previous experience with Ken Dodd had proven he was a capable comedy writer, but the duo weren’t sure his style would suit them. Three well received one-offs allayed their fears and confirmed the beginnings of a very special relationship, although they still had to complete four series on BBC2, before BBC1 was ready to embrace them in colour. So it was not until 8 April 1971 that Cotton started to see a true return on his investment, and by that time he had another significant weapon ready to deploy in his Saturday night arsenal.

Meanwhile over at LWT things were falling apart before they had even begun. The company had stated from the beginning it intended to go its own way and was finding it to be a tough and lonely route. To begin with, the BBC scheduled reams of feature films and light entertainment programmes up against LWT’s Saturday night output. Although effective, this strategy was simply a means to buy the corporation time to piece together what was to become its classic 1970s Saturday night line-up.

Many of LWT’s initial misfortunes were patently not of their own making. The other ITV companies, quick to recognise the strength of the BBC’s weekend output, were reluctant to come to the rescue by exposing their most popular programmes to such heavy competition when higher ratings could be achieved against weaker BBC schedules on weekdays. Granada’s Coronation Street and ATV’s Crossroads were the bankers of the system, but no episode of either was ever screened at the weekend. The fact LWT had pretty much claimed in The Times that the other networks made programmes aimed at morons did little to engender a feeling of togetherness at ITV, but it was hard business decisions that really ensured LWT would have to bear the brunt of the BBC attack alone.

David Frost was later to identify the first seeds of real trouble as being sown by the resignation of their great supporter at the ITA – Lord Hill. Not only did LWT perceive Hill as a powerful ally to be called upon during the battles ahead, he was a strong advocate of the ITV regional programme exchange scheme that ensured the costs of production were fully accounted for by the purchasing company. Upon his departure in 1967, this arrangement was radically altered resulting in a significant decrease in network revenue for LWT, throwing the company immediately into loss, even before it had made it to air.

Other outside influences would add to the strain during the early years of LWT. In January 1972, the government lifted restrictions on the hours of broadcasting, allowing ITV to transmit throughout the daytime hours of the weekdays. An all-day service had already been in place for Saturday and Sunday, however this had traditionally been filled with minority programming that did not attract significant advertising revenue. With the introduction of extra hours in the week though, there was a reallocation of the advertising revenues across the network; with the weekday share rising and the weekend share falling. LWT lobbied that the revenue allocation was now far less attractive than the one they’d signed up for when they had secured the contract. Without Hill, the IBA (the Independent Broadcasting Authority, as the ITA came to be known from 12 July 1972) was unsympathetic.

Starting out with a vision for your TV station is easy. Making it work in the middle of the most competitive point of the weekly schedules is difficult, as is trying to contend with the biggest financial downturn the industry has seen for many years, and attempting to financially operate within an unfair reallocation of your main source of income. However, all of these challenges pale into insignificance in comparison to the personnel issues that come with running a TV station manned by some of the brightest talent in the industry. Idealism in television is a personal matter, and to use it to unify and motivate a team of disparate, intelligent, experienced television people was always going to be a high-risk strategy. This was the challenge for LWT’s first managing director, Michael Peacock.

Right from the start, David Frost found himself irritating his peers and creating resentment by recommending his own programmes to the company. In addition, Peacock was appalled by the amount of money Frost was earning (approximately 10 times his own salary), and quickly the ranks of LWT’s upper management began to congeal into two separate factions: the Frost crowd and the BBC old boys. On the “shop floor” though, things seemed altogether more content – at least to begin with. “We were a hectically busy band of brothers and sisters during those first few months of getting a television station on the air from scratch,” remembers Frank Muir. “I think our state of mind at the time could be fairly described as hopeful, happy and terrified”. Signs of stormier seas ahead became evident to all though on LWT’s opening night.

Frank Muir’s We Have Ways of Making You Laugh had been picked to open the new station. “The show went marvellously,” he recalls, “the full audience laughing and clapping their appreciation … Glowing with sweat and pleasure at the end, I was leaning against a camera feeling happily tired when Humphrey Barclay came up, and said, ‘I have the most rotten news. The show didn’t go out.’” “[The] ACTT (The Association of Cinematographic and Television Technicians) had struck,” remembers David Frost, referring to the union’s threat of action that had come as a result of the franchise changes. “We gradually learned the strike was not continuous, selective, recorded programmes were still getting on air, but live programmes like We Have Ways of Making You Laugh were not”.

Next: “A new kind of game show”