LWT’s output in those early days was as varied as any other ITV station, however the combination of, as David Docherty in his book Running the Show: 21 Years of London Weekend Television puts it, “Brecht, Britten (and) some uninspired situation comedies and uninteresting variety programmes,” along with a number of high-profile live programmes that fell victim to strike action meant that ratings started catastrophically low, and remained that way. On 9 September 1968 (just 18 days into the life of LWT), ATV’s Lew Grade chaired a network programme meeting that was highly critical of the fledgling channel.

Held on a regular basis, these get togethers were designed to allow the heads of the respective ITV regional franchises the opportunity to meet up and co-ordinate their activities, collectively shoring up weak points in each other’s schedules and determining the most appropriate tactics to ensure ratings dominance for ITV. In reality, they were often an opportunity for the old guard (those who had held franchises prior to 1967) to gang up against the brash usurpers. Grade brought enormous pressure on Michael Peacock and Cyril Bennett to dramatically alter their schedules.

As the meeting progressed, it was clear that, on this issue, ITV was split, but by no means down the middle. Granada remained the only company willing to remain supportive of LWT. All of the others expressed a lack of confidence in the station’s output and refused to schedule any LWT programmes in peak-time. Grade enflamed the situation by citing the BBC’s audience share for August as 61 percent (in actual fact, the official figures showed that the corporation had only attained 52 percent), and then capped it all by proclaiming “I got where I am by knowing what I hate, and I know I hate David Frost.”

It was “what the Sunday Times called a ‘Palladium counter-attack’” recalls David Frost, “Cyril Bennett and Michael Peacock were unable to hold the line. Frost on Saturday was moved from 6.45pm to 10.55pm. Michael Parkinson’s Sports Arena was transferred from Friday evening to Sunday afternoon at 2.30, and Southern, Westward and ATV refused to have the Sunday play or the Saturday Frost at all.”

These initial changes were still not enough and the remainder of the year saw a string of scheduling mix-ups. The Franchise Trail – a satire based on LWT’s turbulent birth was deemed by Peacock to be too close to the bone for broadcast during the ACTT strike and found itself persistently scheduled, cancelled and then re-scheduled. Such “censorship” flew in the face of LWT’s claims of being an innovative broadcaster. Matters weren’t helped when the production company actually began distributing pirate copies of the drama on videotape. Similarly, a play containing critical comments of former Labour foreign security, George Brown’s drinking habits was withdrawn by Peacock and Bennett after the ITA demanded cuts. Finally, LWT’s costly “Avengers-beating” action series – The Inquisitors was scrapped prior to any episodes being broadcast because, according to Running The Show, it was just plain “terrible”.

LWT stumbled into 1969 in a fragile state. Michael Peacock’s relationship with the board of directors was becoming symbolic of the company’s perilous situation. Peacock remained convinced he and his colleagues should be left to get on with the business of making television unimpeded by a bunch of money men. The board, in turn was growing concerned that Peacock and his team were ignoring the primary function of any enterprise – to make money for the investors. It is not an uncommon tactic in business to foster team spirit and build up loyalty within a group of people by positioning another part of the same organisation as a threat to the team’s ideals and existence. This is a powerful mechanism, but one that can become self-defeating; particularly when the group identified as the “enemy” hold ultimate control.

Such a tactic worked for Peacock only while his team of creators believed they were producing programmes of artistic merit. The bind for Peacock and Bennett was that even though they did not agree with the board’s view, they could not fail to concede that it was their duty to produce programmes that would attract high ratings; and so far they had not done this. They would have to compromise their artistic aspirations, and in the process risk fracturing the loyalty that had built up within their team.

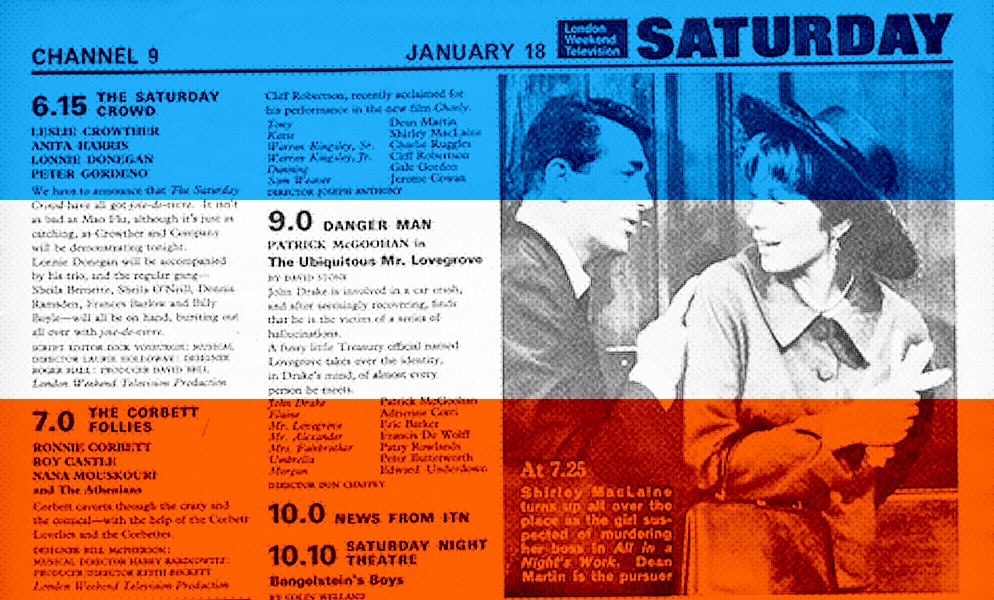

The schedule for January 1969 was far more mainstream – a return to the kind of light entertainment variety diet that LWT had promised to stamp out. The Saturday evening line-up consisted of Leslie Crowther, followed by an imported drama, Ronnie Corbett, a feature film and a late night topical satire programme (made by Granada). While it was generally agreed that the Crowther vehicle was simply not good enough, Corbett still remembers his own programme – The Corbett Follies with fondness. “The idea,” he recalls, “was that I would host the show looking very natty in a fancy dinner jacket or a wild silk suit and I would be fronting a lot of very tall, very beautiful girls … and I would do a few sketches and introduce young American artists, like Henry Youngman or Peter Nero”. The series had been offered to Corbett as part of a deal he and partner Ronnie Barker had struck with David Frost’s production company, Paradine Productions (Barker also got his own LWT show – The Ronnie Barker Playhouse). The duo had first worked with Frost on the BBC programme The Frost Report, and had followed their colleague across to LWT to appear on Frost On Sunday as well as their own programmes. Clearly they, like many others, had seen great opportunity within the fledgling station.

While The Corbett Follies was reasonable enough, and the Saturday line up as a whole unashamedly populist, there was still no significant increase in ratings, and – worse still – there was no let up of external factors negatively impacting LWT. A new ratings system was introduced, and its process of calculating viewers differed from previous measurements – to the disadvantage of ITV. “Furthermore,” remembers Frost, “in February 1969 the companies began to announce their revenue figures on a monthly, rather than a quarterly, basis. This increased the agencies’ tactical room from manoeuvre against the weaker stations in general, and therefore LWT in particular.” It seemed to Peacock and Bennett that no matter what measures they were taking, nothing was working.

“Something has gone crucially wrong with our company,” lamented Humphrey Barclay in a memo written in 1969 to Bennett. Disillusionment was ripe throughout the ranks of LWT’s creative talent, with many appalled at the apparent disregard for the vision that had driven the company’s formation. Bennett’s response (delivered via a press conference on 3 July) was to assert that “the first duty of a commercial station is to survive”. This was taken as an admission of a major downsizing in LWT’s artistic ambition, and served only to disgruntle the “BBC3” contingent even more. In the middle of the rancour, Frank Muir pressed on oblivious of what was going on around him. “Everything now in LWT seemed to be going so well,” he remarked of mid-1969. “My department had the usual complement of failures, but also some stunning successes, three of the shows ran for years and there were plenty more in the pipeline.” Muir’s life at LWT seemed to consist of visits to Russia, or Buckingham Palace, gentle reciprocal mickey-taking with his staff, and space and authority to make whatever programmes he wished. In retrospect, Muir’s LWT experience, although contrary to everybody else, suggested the original LWT vision might have been sustainable after all.

Now partly based in New York, David Frost looked on with mounting frustration. He was aware to some degree of the problems back at LWT, and to him, Peacock was most at fault. “Michael’s relationship with the board had become a dialogue for the deaf,” he observed. “He regarded almost anything that the members of the board attempted to do … as unjustified interference. The board in their turn looked in vain for a sign that Michael and his management team had the skill and experience to respond to changing circumstances. As someone who had recruited many of the members of the board, I found this gulf particularly sad, and worse still totally avoidable.”

“Then,” recalls Muir, “the whole thing suddenly fell apart”. In August The Sunday Times published a damning report, in which they compared the promises made by the new ITV franchise owners against what had actually been delivered. None of the new stations was considered to have fulfilled their obligations, but LWT was singled out for special criticism. How much of the report was fuelled by a desire to bring the station down a peg or two is difficult to determine; whatever the motive, the piece had a dramatic effect, precipitating the final downfall of the high-minded LWT that had been presented to the ITC back in 1967.

Michael Peacock grew ever more belligerent as his position became under siege. Not only was his relationship with the board and his staff now at an all-time low, he was disliked by many within the other ITV stations too. His continual attempts to have advertising revenue re-allocated (to the benefit of LWT) plus protestations at the poor scheduling of LWT programmes by the other regions and their unwillingness to schedule their top rated programmes on a Saturday night, meant that whenever LWT was mentioned at a Network Programme meeting, lengthy and bitter arguments would inevitably break out. To cap it all, the advertisers objected to Peacock’s high-minded approach, commenting that he found the whole notion of advertising reprehensible.

Next: “Synthetic propensity”