The failure of Bruce Forsyth’s Big Night was a major blip for ITV, but not an outright disaster. On the plus side, Michael Grade was proving to be a great success as LWT’s director of programmes. Not only had he succeeded in poaching Bruce Forsyth from the BBC (which was still a coup regardless of the failure of Big Night), he proceeded to run LWT like (according to the then director general of the BBC, Alasdair Milne) the “mafia with a cheque book”. Grade almost succeeded in stealing Esther Rantzen (then at the height of her popularity with That’s Life!) and successfully lured Dennis Potter away from the BBC. In November 1978, Grade infamously negotiated a £5.5 million deal with the Football League for three years’ exclusive rights. He also oversaw the creation of a number of original and highly popular programmes for LWT, including It’ll Be Alright on the Night (1977) and Mind Your Language (1977) – both of which drew in more than 18 million viewers, in the process adding enormous weight behind ITV’s Saturday night ratings battle with the BBC. There were however two significant factors that ITV had to contend with at the end of the 1970s. The first was the impending franchise renewals that were scheduled to take place during the middle of 1980. The second event was less clearly signposted. It occurred at the end of 1979, and resulted in the network coming off the air for 11 weeks.

The relationship between the unions and the television bosses had been at a very low ebb throughout the preceding 12 months leading up to the industrial action of 1979. The mood at the 1978 Edinburgh Television Festival was particularly sour, with a session instigated by television producer Jeremy Bugler, that unveiled the deepening but publicly-unexpressed concerns among programme makers that trade union restrictive practices were harming programmes. The view Bugler advanced was manifold: unions were making demands for huge and unwieldy crews; technicians were being paid to sit in hotels in faraway places – but not to work; overtime multipliers and escalators; and a blacking of new equipment. Alan Sapper, then head of the ACTT, was quoted in the Festival programme as saying: “£2m of technology lying unused! Good! That’s a victory for us.” John Birt, then at LWT recalls “we were a grotesquely fat and wasteful industry, inefficient in our use of money and resources. Though we did not then appreciate the awesome scale of our wastefulness”.

Michael Grade remembers with some contempt that the ACTT could make any demand they wanted of their employers, such was their power; and to his mind they routinely set about abusing this situation. “All of us were demeaned,” he asserts “by the necessity of adding bribes to high wages to get technicians to work.” Formed in 1933, the Association of Cinematograph Technicians first embraced television in 1956 and fought to secure recognition from the BBC for its members. Although unsuccessful, it was recognised by ITV. Alan Sapper assumed the position of general secretary in 1969 and grew to become a figure, equally loved and despised in the industry.

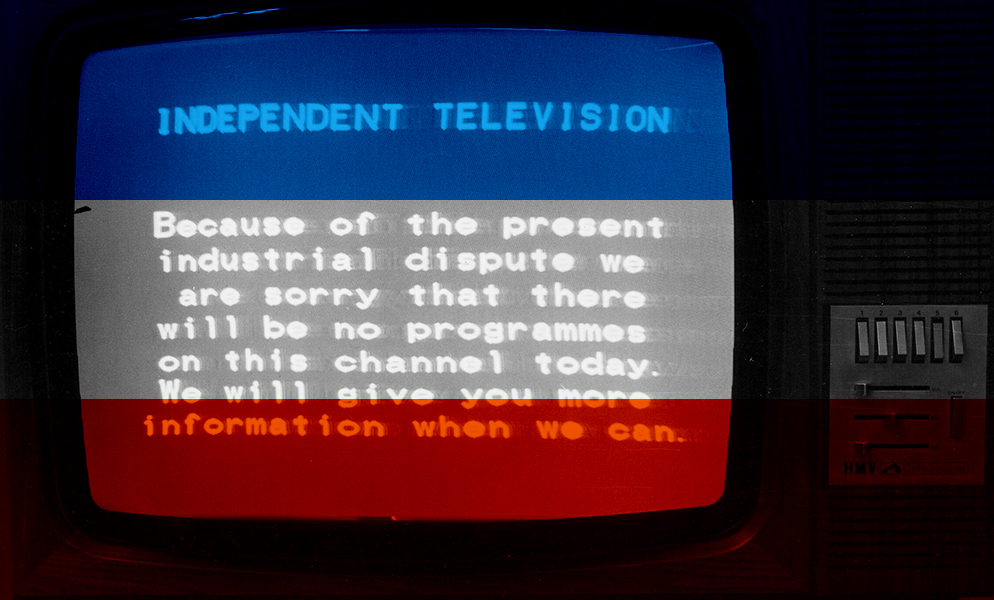

In 1979, ITV decided to make a stand and during the round of wage negotiations rejected the union bid. Instead of putting up any kind of protracted argument, the ACTT pulled the plug on the network, leaving ITV facing a black out. “Airtime was an irreplaceable asset,” explains Grade. “If we lost any of it through disputes, we forfeited the advertising slots that went with the programmes that had not been transmitted. Unlike newspapers, we couldn’t print extra pages to accommodate any advertising that had been lost. The IBA would not help by allowing us to sell alternative advertising time. Their position was simple. They believed the public interest was best served by keeping the screen alive, so we must accommodate the unions at whatever cost to ourselves.” Consequently the final settlement – 11 weeks in to the blackout – resulted in Sapper securing an even larger pay increase than originally asked for.

The strike of 1979 was to be the last hurrah for the ACTT. Although they would again cause serious difficulty during the early years of TV-am, the BECTU (Broadcasting Entertainment and Cinematograph and Theatre Union) website records that “the period since 1979 has been a critical one … Hostile government legislation, technological and structural changes in the industries in which they organised, sustained attacks by employers on the employment, contractual status, pay and conditions of service of union members have left BECTU with a paid-up membership significantly smaller than the 60,000 or so members collectively claimed by ABS, ACTT and NATTKE in the early 1980s”. While many of the measures taken against trade unions by the Thatcher government were designed to specifically weaken transport, fuel and steel, some of the specific legislation brought in had its most profound effect on the entertainment industry.

“For example,” recalls Motion Picture Editors Guild executive director, Ron Kutak, “the union cannot strike for recognition in order to obtain an agreement. This means that if the employees of a company want a contract, they cannot strike to force the company to negotiate with the union. Instead they must schedule a ‘ballot for industrial action’, which, in the case of a theatrical or non-series television product, sometimes cannot take place until after the show has wrapped production”. Such was the state of television unions by the start of the 21st century, a BAFTA symposium with BECTU chose to debate why the union refused to let its members work on films without pay. “It was difficult for me to witness,” reflects Kutak “and vividly demonstrated that a hobbled union not only weakens the terms and conditions of all film and television employees, but worse, cheapens and devalues the craft itself”. Of course others disagree, and Michael Grade for one believes that “whatever may be said of the Thatcher regime in general, there is no doubt that through her trade union legislation she saved more than one industry from medieval servitude.”

Meanwhile, the BBC was predictably exploiting ITV’s failings wherever possible, and the final few Saturdays of the 1970s saw the corporation wipe the floor with its commercial opposition. A line-up that consisted of Basil Brush, Doctor Who, Jim’ll Fix It, All Creatures Great And Small and Dallas had every right to stomp all over such lacklustre offerings as The Practice, The Allan Stewart Tapes and Search for a Star. However, this domination was compounded by the fact that audiences had grown accustomed to the BBC’s offerings and had forged a new loyalty while ITV had been away.

Next: “Hands up those who couldn’t care less”

Glenn A

October 21, 2017 at 2:02 pm

I can only remember watching ITV’s dramatisation of Dick Barton( very underrated) and Dick Turpin on Saturday evenings on ITV in 1979, before switching over to BBC1 for Doctor Who and not changing back. There was just nothing they showed that was worthwhile compared with the BBC’s comedy, drama, imports and light entertainment. A few years later, though, and I was just as likely to watch ITV as BBC1 on Saturday nights as ITV had really upped its game and the BBC schedule had been weakened by moving Doctor Who and losing Parkinson.