|

|

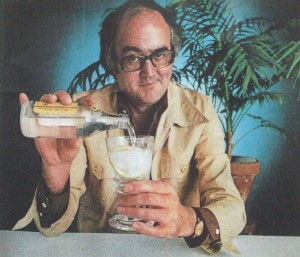

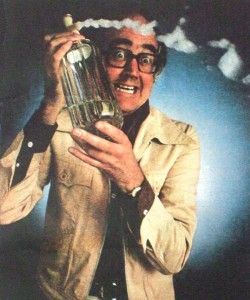

WHEN TV frontmen are metaphorically bottled off the screen, it’s usually either for being patronising or being too clever by half. Only JAMES BURKE has ever been hounded away from Television Centre for being both simultaneously. A jobbing translator of encyclopaedias in Italy, Burke chanced upon a job ad for a TV report on the Mafia, went for it, fumbled his chance, but still managed to hook up with the Beeb’s nascent science programme TOMORROW’S WORLD, despite being, in the Burke parlance, a strictly humanities kinda guy.

Offsetting the patrician tones of TW kingpin Raymond Baxter with what one hack labeled his “aggressively street-speak screen style,” Burke got younger viewers hooked on the early evening carnival of white heat gadgetry, and when the Apollo moonshots came along, he was there front and centre. Sometimes broadcasting for thirty hours at a stretch, he became a propane tank-dissecting household name, “the one contradiction to the rule that over-exposure on TV can kill a personality”. To put the old tin lid on it, in 1969 the Birmingham Ophthalmic Information Council voted him “Britain’s Top Man in Spectacles”. Burke could do no wrong. Now all he needed was a show of his own.

The Burke Special (1972-6)

Burke’s first name-above-the-title gig took up the TW Thursday night slot, and was a sort of extended “Tomorrow’s World plus”: an illustrated lecture in front of a studio audience on a vexed topic of modern life, with a few guesses as to where it might be headed in the future. Or, as the publicity put it, “an oblique look at modern living.” “Oblique” meant something like “sideways, but without the jokes”, as Burke conjured up his own, mildly hysterical brand of futurology. ID cards, zero population growth and a plug-in super teacher for every child would be with us, he promised, by 1993, while demonstrations leapt all over the place, from magnetic bubbles to miniature cauliflowers, and God help the viewer whose brain was too slow to keep up.

Some loved it, plenty hated it. Specials on test tube babies and gun control caused big controversy. With the populist likes of QED still a decade off, science broadcasting remained an acquired taste. But whereas the likes of The Sky at Night were akin to a fine sherry, The Burke Special was neat bourbon in a pint mug. Cocksure, belligerent and bursting with enthusiasm in his trademark white safari suit, Burke ripped through an often nightmarish vision of the future as if he couldn’t wait for it to happen. High-backed armchairs in Leatherhead creaked with palpable unease.

|

|

Connections (1978)

Then they relaxed somewhat as Burke disappeared from the screen for two and a half years. The bad news was, he’d spent that time planning his meisterwerk. The cramped studio environment was bid adieu as Burke rattled through 150 location shoots in 20 different countries to piece together what the Beeb assured us was his Civilisation, his Ascent of Man. But when Burke announced that, instead of covering the Renaissance masters or the discovery of classical geometry, he would be concerning himself with such esoteric matters as “what has the recipe for Chicken Marengo got to do with air conditioning?”, the squeak of Home Counties armrests was deafening.

James Burke’s Connections: an Alternative History of Change, to give it its full title, was so unlike the standard flagship documentary series that Burke found himself using up most of the first edition explaining what it actually was going go be. Each programme was to carve its own merrily esoteric path through the history of technology, starting off, say, with marine compasses, before moving onto sulphur, cloud chambers and ending up at a relatively modern invention like the atom bomb, through a series of counter-intuitive leaps, or connections. And to keep the audience watching, Burke would lay subtle clues as to the identity of the final invention, “what this programme is really about”, along the way. “As much Raymond Chandler as BBC Science Features”, as the man himself put it. What was more, the programme was not intended to be the definitive work on the subject. After all, connections could, Burke insisted, be made between just about any two historical phenomena you might choose, if you looked hard enough. So these ten programmes were just a handful of the many thousands that could be made. As you might expect, this didn’t sit too well with the Bronowskians. How much was this costing again?

But as far as they were concerned, the main problem remained Burke himself. Brusque, confident, self-propelled, he tore off round the globe in pursuit of his own agenda, in a way the established BBC documentary audience wasn’t quite ready for. He didn’t quite conform to the “eccentric” pigeonholes TV had thus far created for presenters. He was neither unflappably authoritative like your Kenneth Clarkes, nor was he a comic turn in the sense that Patrick Moore or Magnus Pyke were – acknowledged masters in their esoteric fields who nevertheless showed every sign of being in dire need of air sea rescue were they to be left unchaperoned with such arcane devices as a launderette or a pay phone.

In short, Burke was an eccentric, but one that demanded to be taken seriously. And on British telly, you couldn’t have it both ways. Detractors cheerfully admitted they didn’t have a clue what he was on about, but that was his problem, not theirs. Forever questioning himself out loud, swapping locations (sometimes in mid sentence), or suddenly negating what he’d been saying for the last minute by purposefully walking off screen, then ducking back into shot with a casual “except, that last bit isn’t true at all”, he wound up the Bronowskians something chronic. “If even he’s not sure what he’s on about,” went the argument, “why the hell should we be paying to watch him wittier on?” They were missing the point somewhat – the randomness and complexity of civilisation was precisely Burke’s main argument – but Connections set the bizarro persona in stone. By the time Not the Nine O’Clock News captured the Burkeish self-inquisition with typical deftness (“Good evening. Or is it?”) he’d become a national treasure, albeit one a significant minority wouldn’t mind seeing pawned to help buy Robert Robinson a new blazer.

|

|

The Real Thing (1980)

No doubt aware of his growing band of armchair enemies, Burke responded to the naysayers in typically counter-intuitive fashion – by becoming more Burkeish than ever before. The Real Thing was all about the perception of reality, a field which proved a veritable playground for his sprightly imagination, and he duly cut loose with gusto. Or, in his own words:

“You probably think you need a series of programmes on reality like a hole in the head. I mean, you know what it is, I know what it is, and only a lunatic would question the matter. So why am I wasting your time? Well, on the subject of lunatics, let me suggest this: the only accurate thing that can be said about people who think they’re poached eggs is that they’re in a minority. And what I hope this series will show is that as far as everyday living is concerned, we’re all poached eggs, in a manner of speaking.”

Well, you couldn’t say the viewer didn’t know what to expect. True to his word, Burke lectured the camera while playing guitar, hanging upside down, interacting with dancers dressed as shop window dummies, wandering around life-size optical illusions and, in one memorably brain-frying edition, presenting the programme from a NASA-like control gallery, which turned out to be situated, Numbskulls-style, in the centre of Burke’s own head. Little Burke looked wryly on as Big Burke mooched around a swanky NW1 party, noting the bursts of frantic action occurring in mission control every time he made a lunge for the peanuts or failed to cop off. By that point, of course, only hardcore Burkeheads were still watching, but there were still just about enough of them to guarantee a recommission. The question was, where to go next?

|

|

The Day the Universe Changed (1985)

As the eighties sped on, there was less and less Burke on the Beeb. 1982 saw one-off brain exposition The Neuron Suite, in which Burke jumped with both feet into the realm of self-parody, explaining how the human cortex functioned by likening it to a five-star San Diego hotel – into which, naturally, he checked, bumming about in his luxury room with various bits of LED-festooned papier-mache, and even fiddling with a SIMON toy at one point – all in the course of viewer education, natch. Then radio silence descended once more, as he combined rent-paying outings for the Central Office of Information (oh, to be a town planner and get paid to sit and watch At Last… It’s the Traffic Management Show!) with yet another great big ideasfest.

Billed as the third in the “Connections trilogy”, TDTUC was actually more of a retread of the Connections format, this time with the emphasis on scientific discoveries influencing philosophy, “because if you don’t know why things have turned out the way they have, you haven’t a hope of understanding the crazy, fast-moving circus we live in”. So Burke did his by now standard jet-setting monologuery, telling of how Galileo’s observations screwed things up for the Catholic church, etc. Otherwise, things were all as normal aboard the Burkeship, even (whisper it) slightly more sober and conventional than in past excursions. Only slightly, mind. Viewers, feeling they’d seen it all before, were less enthusiastic this time out, and by the time he rounded the whole thing off by babbling on about some nonsense future where all the world’s computers would be connected together, providing a gigantic resource of free information, the scope of which the humble folk of 1985 could hardly conceive, a cost-conscious BBC management were quietly pulling the plug on our man. He’d crop up again, in books and journals, and punting out more series of Connections for the Canadians, but as far as British mainstream telly was concerned, Burke was a poached egg on toast.

To be fair, he was rendered obsolete largely by his own innovations. Burke always protested that his brand of Puckish enthusiasm would never be fashionable, but prime time was increasingly proving him wrong. Ever since Connections took off, “quirky” science had been increasingly seen as the thing to do. Horizon was the first to have a bash, roping in folk like Dudley Moore for quizzical, self-contradicting romps through the realms of time, dreams and so forth. Then came QED, which was at least 50{30e2395aaf6397fd02d2c79d91a1fe7cbb73158454674890018aee9c53a0cb96} full of Burkeish whimsy. As the decade matured, with the likes of The Show Me Show and Bodymatters filling the studio with polystyrene cross sections and optical tomfoolery, practically everyone was documenting science the Burkeish way. Of course, this means he’s also indirectly responsible for Bang Goes the Theory and That Thing With the Pranny off of Top Gear, but some connections are perhaps best ignored.

Burke! Feed Me!

June 30, 2010 at 11:05 pm

Apart from the bits described above, I also recall when James was showing how the brain worked and would flash images on the screen that were supposedly his own thoughts. When he saw an attractive woman, he pointed out his mind turned to the sexual, so the quick montage was of a bunch of naked women, something I found quite shocking at the time. Innocent days.

Glenn A

July 1, 2010 at 5:48 pm

You never knew what to make of him. He was a very intelligent man but he certainly made you know it and for all his series were beautifully filmed at great expense, they were just too OTT and seemed to go over most people’s heads. I do recall my parents, who certainly weren’t thick, switching off The Day The Universe Changed as a lot of pretentious, boring twaddle. Certainly looking at clips now I will agree it rambled on at great length and was difficult to follow, but had someone like David Attenborough made it the series would have been hailed as a masterpiece. However, Burke, an Ulsterman who wasn’t a trained scientist, was always going to be an outsider.

paulus - bangkok

July 2, 2010 at 5:49 am

He survives on Asian Discovery networkl: science channel.

Hardly a day goes by without some eposide of “connections” being on the TV.

Considering that this was early 70’s I am surprised how well the production looks today.

Of course, now that top-gear/crash test micro cabbage is remaking it under his own brand… BBC couldn’t have disliked it that much.

Alan Bourke

July 2, 2010 at 2:18 pm

I loved, loved, loved Connections, had the book and everything.

Not The Nine O’Clock News spoof:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=82GUX_NA7AU

Glenn A

July 2, 2010 at 6:22 pm

Ho, ho, Alan, Burke as most viewers saw him, an OTT more intelligent than you presenter of bizarre programmes that were an acquired taste. It’s been red hot in Whitehaven today, but was it, actually it was the dawn of a new ice age, etc, etc.

johnnyboy

July 3, 2010 at 11:31 am

There was a Connections article in the Scientific American magazine for a while written by himself, i think in the late 90’s. Don’t know when it stopped.

Also one part of “The Real Thing” I thought was cool was his description of sight, and how it can be fooled (the upside-down glasses for example) and one you can even try now – look at something, then move your eyes rapidly to look at something else without moving your head. You never get to see what’s in-between the objects you are looking at, your brain just blanks it out. Amazing! But I never noticed until James told us on the telly. Actually I tried this whilst at work one night and doing the same as the above passing my vision over a fluroscent clock display – the numbers in the “persistence of vision” part of my sight were seen to be backwards!! Go on James, explain that one!

Isn’t science wonderful (apart form nuclear weapons – which James went on about as well, but I digress).

Glenn A

July 4, 2010 at 4:56 pm

In his defence he was good on Tomorrow’s World and for a non scientist he took to his chosen subject with real enthusiasm.

tomnamoon

July 13, 2010 at 4:57 pm

I just wonder now, that after watching watching the ‘Connections’ (5Stars)

series on y’tube, that James Burke is responsible for originating a fear of the unexpected withdrawal of technology from our lives. My Mum would have gone mad at the gas-stove without Volta’s pistol!

Glenn A

July 17, 2010 at 6:35 pm

Also, did Burke once advertise Timex watches on a set that resembled The Burke Special?

pessoa

July 18, 2010 at 12:46 am

This bit where he synchronises his talk with a rocket launch has great panache

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TcBGpcFwung

I also found that while I enjoyed it at the time,my parents thought it was pretentious and overcooked. With hindsight some of the ‘connections’ are a bit shaky, but he seems a sincere man on a mission to explain, like other good documentaries of that decade.

Adz

August 20, 2010 at 10:31 pm

I seem to remember one episode which involved women in medieval dress stripping off and jumping into wooden bathtubs, and then the great man illustrating advances in warfare with wargaming, both of which were very appealing to this (at the time) ten year old!

I also recall one of Burke’s wonderfully prosaic truisms:

“this desk – is plastic; this phone – is plastic; MY SHIRT – is plastic”!

Pingback: Cheese and Wine « mud-brick.com

Gerry Dorrian

May 1, 2012 at 10:03 am

Recently the BBC aired TV 73, including a clip from The Burke Special where Burke showed how a radio-controlled car could be used to detonate a bomb. Is it totally coincidental that the Luton terrorists were planning to use such a car?

Thomas Worthington

July 17, 2012 at 8:01 pm

The first episode of Connections, with the wrecked motorway and the deserted farm is still one of the most powerful pieces of documentary filming I’ve seen (Descent of Man’s speech culminating in the muddy remains of the presenter’s massacred relatives being #1) and has shaped my whole adult life.

Great stuff and I for one miss him.

bob Mclintock

October 27, 2012 at 12:15 am

Loved the series as a kid…but it only really works in a world before rewind. Looking upon it as an adult he was very loose to say the least. Association is not causation. On his web site he links Corn Flakes to Carl Marx, it is frustrating because his idea of non-linear history is something that should be taken seriously. But he is so sloppy with his own metheodology.

Bill Hedley

August 22, 2013 at 9:09 pm

Wonderful analysis! I loved James Burke. I was working at Lloyd’s of London in the late eighties or early nineties and I went down into the Underwriting Room one lunch time and there he was, in a white suit, with a film crew. “Great,” I thought “we’ll see him back on TV soon”. Bet we never did. Not in Britain, anyway.

Thomas Worthington

July 19, 2015 at 9:50 pm

Connections was life-changing TV. The first episode in particular changed my view of the world profoundly and still informs my thinking on things like the Greek Euro-crisis today. Horribly overlooked for a knighthood, given that 3rd-rate know-nothing civil-servants get them just for keeping their mouths shut for 30 years, not to mention footballers.

Nick Kirby

December 2, 2015 at 1:08 pm

Loved Connections when I was a youngster – wish I could get it on DVD. I also recall being a star-struck eight-year-old when I nearly accidentally walked into him in Canterbury Cathedral in the late 1970s.

Barbara Arnzen

June 10, 2016 at 12:27 pm

I remember seeing Connections on PBS in the 1980’s and I just ate it up. Maybe because my mind can take in a lot of information at once (I am the 7th of 13 children), I immediately understood Burke’s style and appreciated his sense of humor. I am now finishing off his series (per Netflix) The Day the Universe Changed and I am enjoying it nearly equally to Connections. In my opinion, we always need offbeat and intelligent people like James Burke to help us to think more.

Glenn Aylett

October 3, 2021 at 2:53 pm

James Burke must have cost the BBC a huge amount of money as he loved jetting around the world as much as Alan Whicker to prove such bizarre things as Galileo started the Reformation. Problem was, it was like the BBC had indulged a mad scientist or an Oxbridge don with programmes that became more and more unwatchable. I do recall Universe being slated on Points Of View and the Radio Times letters page for its massive cost, its impenetrable subject matter, and the fact it was a boring ego trip for the presenter.