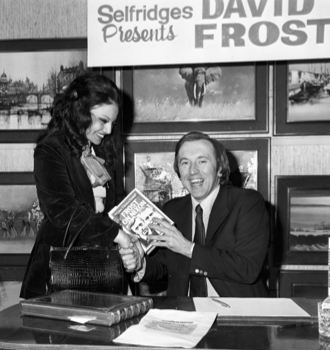

FEW WENT ABOUT THE BUSINESS OF BEING FAMOUS as meticulously as David Frost. Even fewer managed to make it look so effortless.

From his debut on television in 1962 to his unofficial retirement in 2005, everything seemed so maddeningly playful. A whiff of insincerity, a sense that he wasn’t merely the sum of his parts but that his parts weren’t even his own, clung to him throughout his TV career.

Yet he virtually created the modern media industry, if not purposefully then through intimation. Both on and behind camera he revolutionised what was possible – and more importantly what was thought possible.

From the start it all seemed casually calculated: an attitude that won him as many apostles as brickbats right up to his death. The job fronting That Was The Week That Was came about partly because John Bird didn’t fancy it, but mostly because of a nice lunch between Frost and the show’s creator Ned Sherrin. Frost was inserted into a format 95{30e2395aaf6397fd02d2c79d91a1fe7cbb73158454674890018aee9c53a0cb96} fully-realised. But he contrived to make the remaining 5{30e2395aaf6397fd02d2c79d91a1fe7cbb73158454674890018aee9c53a0cb96} the most important bit of all: himself.

Christopher Booker said Frost’s most obvious quality was “he simply wanted to be amazingly famous for being David Frost.” Yet away from the cackle and the hair, Frost turned in some remarkable work.

Christopher Booker said Frost’s most obvious quality was “he simply wanted to be amazingly famous for being David Frost.” Yet away from the cackle and the hair, Frost turned in some remarkable work.

For example, there remains very little on television that has ever been as incisively critical as the sketch on home secretary Henry Brooke broadcast in the very last TW3 in December 1963.

Its effrontery is staggering. Brooke is paraphrased as being “the most hated man in Britain”; he is called a liar; Frost declares: “Your word, Henry, isn’t very eloquent, is it? Perhaps that’s why you so rarely bother to keep it”; and it ends with Willie Rushton as Brooke saying direct to camera: “It just shows, if you’re home secretary, you can get away with murder.”

Frost didn’t make TW3, but it made him. In turn he made a whole host of others if not quite as influential as he, then certainly as famous.

The casts and writers of TW3, its successor Not So Much a Programme, More a Way of Life (1964-65), and the subsequent comedy series The Frost Report (1966-67) were the yeast in British TV entertainment of the 1960s. Frostie had the wherewithal, but also the intelligence, to fuel the rise – and to ensure he rose with them. The whole industry got shaken up.

Ubiquity became the trademark. For a time he was on television every night of the week: four in America, three in the UK. If you had the means, you could arrange to be out of the country whenever he was in. If not, he was there to shoo you to bed with an increasingly cosy turn each Friday, Saturday and Sunday.

Now he was playing television like a captain of trade. He owned the commanding heights and became the champagne commissar of ITV, pulling levers and spinning dials and concocting five-year plans. The industry got shaken up all over again.

And still he couldn’t really do presenting. The topical gags at the start of each edition of Frost on Sunday (1969-72) triumphed in spite of their delivery. Frost would appear, his grin and tie perfectly in place, gripping a clipboard a little too tightly, armed with zingers penned by Dick Vosburgh and Neil Shand about statutory incomes policies or the Common Market, only to plunge through proceedings with the same demeanour as a Wile E Coyote plunging down a ravine.

Did it matter? Not a jot. It never mattered. The material made the man, not the other way around. If the material ever ran out, so did he.

Did it matter? Not a jot. It never mattered. The material made the man, not the other way around. If the material ever ran out, so did he.

The best moments in Frost’s interviews came when the scripted questions led into chit-chat, combative and wispy. It was here that he let his knowledge of both medium and message inform his interrogation rather than dominate it.

The jousts with Nixon and Kissinger would not have so wrongfooted their subjects had the host not been so lightfooted in his prosecution.

The showdown with the Yippies would not have worked in any other setting than a studio, where Frost could nail so perfectly his cluster of undignified dopes by informing them: “Laughing childishly when you manage to say a four-letter word on television? Big deal.”

When he told Emil Savundra that he had “either to be stupid or dishonest – which?” it was a question Frost could only have asked on live TV with a garrulous audience egging him on and a larger one at home hanging on his every word. “Well done Frostie!” the studio cried as, shuddering with rage, he strode off set as the credits rolled, surely knowing that such a denouement would have just as much impact as the cross-examination it concluded.

The language of television that Frost helped to write was easy to mock at the time, but only in the way anything unfamiliar is lampooned in order to make it more palatable. The parodies came quickly too, with former proteges leading the charge.

Monty Python’s Flying Circus spoofed Frost with the kind of barbed wit based on first-hand experience. But listen to the hoots of laughter and applause from the audience as they realise who Eric Idle is impersonating. This is no elite in-joke. Everyone is in on the gag – and it’s only 1970, not even 10 years into the Frost supremacy.

“David came over here and fooled everybody for a while,” said Johnny Carson. “They thought he was an entertainer – and then they got on to him.”

“David came over here and fooled everybody for a while,” said Johnny Carson. “They thought he was an entertainer – and then they got on to him.”

Frost’s strutting around the planet in the 70s stretched the elasticity of his act until it was nearly transparent. Those who wanted to could look right through. Others marvelled at how he kept it all together.

The scrupulous gadabout was once again shaking up the industry, this time on a global level. He funded and filmed the Nixon interviews independently, raising an imperial two fingers at the US networks. He then sold the tapes to whoever was interested, being sure to keep hold of the rights. And still the money bubbled in.

There was no science to any of this. The one time Frost tried to dabble with the elements with was when he promised “sexual chemistry” at TV-am. That particular farrago was one from which he managed to emerge with his status and bank balance reasonably intact.

But from now on a different kind of Frostie flitted through the ether. All the rough edges had been chipped off. Where once he sashayed, now he shuffled.

Come the 1980s, all most of us saw of him was an hour or so on a Sunday morning, and the occasional Guinness Book of Records special on a bank holiday. He was still only in his 40s, but like Keith Richards and the Queen he suddenly seemed to age 30 years in the space of three.

Then, as if to prove such cheap observation wrong in as public a manner possible, he had one last go at shaking things up. Except this time, he over-reached himself in spectacular fashion.

“Richard Branson and I have always cherished a desire to work together,” Frost said when trying to explain the reason for their joint attempt to win yet another slice of ITV in 1991. The bids were stuffed with ponderous quotations from ancient philosophers. Money splashed about the place, with £45m being pencilled for London, £22m for the south and £10m for East Anglia.

Yet it wasn’t the cash that scuppered the project. All three bids failed the meet the regulators’ “quality threshold”. In other words, they were rubbish. With proposals including “Sunstroke, set in a ClubMed-style resort”, an adaptation of Jeffrey Archer’s Beyond Reasonable Doubt and 60 minutes of local news a night, it shouldn’t have been a surprise. But it was unusual to see Frostie fail. Twice, in fact, for the same process saw TV-am lose the breakfast franchise.

A berth on the BBC completed his journey from industry ignition to brake.

A berth on the BBC completed his journey from industry ignition to brake.

Breakfast with Frost was where things simmered down, not kicked off. It was sofa, so good. The drowsy atmosphere sometimes lulled politicians into indiscreet outbursts. This was the exception, however. The programme was an anachronism from the start: a 1950s colonial-drinks-lounge supposedly at the spearhead of a 1990s mission-to-explain Birtist BBC.

It did change over time, but only to become more cumbersome, fussy, peculiar. After the final show in 2005, the continuity announced proclaimed it to be “the end of an era”. Whichever era it was, it was the wrong one.

For what will David Frost be most remembered? Almost certainly the shop-window stuff: the chinwags with potentates, the tete-a-tetes in presidential parlours, the way he made satire look glamorous and sexy rather than starchy and sad.

But he also deserves to be cherished for his appreciation of how television works, what makes it great, and how it can confer greatness upon others.

He created the template for the modern media mogul. He showed that you can be on TV and run TV at the same time.

Above all he understood what countless others failed and still fail to realise: that it’s not what to be on television that matters, it’s how.