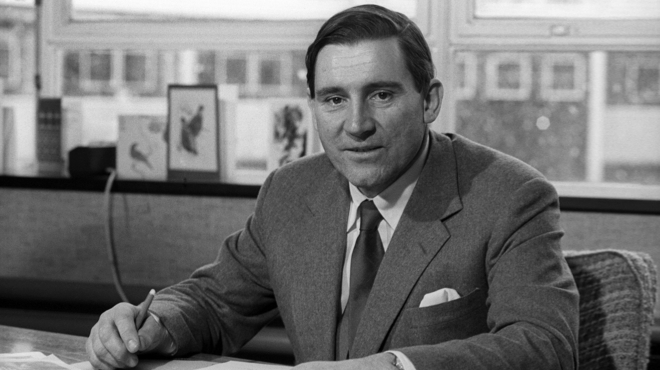

A tribute to the former BBC director-general, who has died aged 82.

When the BBC board of governors were looking for a replacement for outgoing director-general Ian Trethowan in 1981, despite Alasdair Milne (as deputy director-general and managing director of television) being the obvious successor, they still went ahead and placed advertisements in the newspapers seeking “recommendations and applications”.

Intent on highlighting the absurdity of this situation, Bill Cotton went along for an interview, not to put himself forward for the role but solely to “recommend” Milne. The bemused governors eventually gave Milne the post he’d been tipped for ever since joining the Beeb in 1954, but their deliberations uncannily portended five years of unprecedented – and wholly unforeseen – turbulence that would ruin the man’s career.

Milne had shot up the BBC ladder, working to create TONIGHT, THAT WAS THE WEEK THAT WAS and THE GREAT WAR before serving time as controller, Scotland and director of programmes, television. Neither a visionary in the mould of Hugh Carleton Greene, or a networker like his immediate predecessor Trethowan, as DG Milne inspired only qualified loyalty from his staff: a situation that evolved out of the man’s own enigmatic personality.

He addressed other colleagues as “Boy”, preferred settling awkward personnel issues over a glass of whisky, and had a very small, tight circle of friends. Michael Grade, as controller of BBC1 and director of programmes, was only invited to his office twice in three years – and one of those was to be interviewed for Milne’s job.

But Milne adored the BBC, and managed to build one of the best management teams the organisation had ever had, with figures such as Grade, Cotton and David Hatch heading up a team who’d spent up to four decades mastering their craft and serving the Corporation.

Trouble was looming, however, in the shape of an anti-BBC lobby more spiteful and sustained in its criticism than ever before, regardless of the fact the Beeb was delivering some of its finest drama, comedy, current affairs, children’s and factual output. When the machinery of BBC governance, very carefully and smoothly oiled by former DGs Charles Curran and Ian Trethowan, became unstuck, everything reached a head and relations between the governors and the Beeb’s management fell into pieces.

A sequence of controversies, mistakes, misjudgments and bad luck pock-marked Milne’s tenure as DG. Some were revisits to old ground trod by Trethowan (how to cover Northern Ireland), Hugh Carleton Greene (standards of morality) and even Reith himself (the point of the licence fee).

But others were unavoidably contemporary. A terrible catalogue of misfortune blighted the Corporation in the mid-’80s. In short, the governors, led from 1986 by the menacing Marmaduke Hussey, saw everything as being the fault of Milne personally, and became obsessed with contriving his departure.

In one sense Milne was responsible: he was the editor-in-chief, accountable for everything broadcast, transmitted and published in the BBC’s name. But a figurehead is not the same as a scapegoat. To ascribe Milne culpability for all the Beeb’s failures was as ludicrous as giving him sole credit for all its successes. When it came to the fight, however, Milne simply didn’t have the stamina to prolong his survival. His lifelong preference for negotiation and compromise over fortitude and aggression ultimately accelerated his own fate.

In the end Hussey and his deputy Joel Barnett virtually removed Milne themselves, collaring him after a board meeting on 29 January 1987 and, presenting themselves as “men of honour”, ordered him out, agreeing to dress the entire charade up as a resignation. A flummoxed Milne made no pretence of objecting, or of wishing to consult colleagues over the legitimacy of his dismissal.

This same passivity permeates Milne’s autobiography, where not only does he leave the circumstances surrounding his sacking to the very last few pages, but chooses to sum up the pivotal, dreadful confrontation with Hussey and Barnett in just five words (“What terrible people, I thought”).

By any measure, Milne’s exit was a tragedy. His successors worked hard to hasten his total expunging from the BBC’s history – a process the man, with typical perversity, seemed happy to encourage.

Disappearing into almost total obscurity, Milne takes to his grave the details of precisely what happened that day in January 1987.

His name, and work, was all-too quickly forgotten, but not just thanks to the passing of time: those forces who had chased him out of the BBC re-focused everyone’s attention away from Milne’s demise by perpetuating, not healing, the rancour. The Corporation is still dealing with the legacy of those events today.

Glenn A

March 10, 2013 at 11:16 pm

Also the second Scot to hold the DG’s job. Not bad, but he should have hired Michael Grade earlier as he persisted with the dire Alan Hart and Aubrey Singer for too long, when clearly they weren’t up to the job. However, when Grade and Cotton came to save the BBC’s ratings bacon in 1984, they transformed it and by the time he retired BBC Television’s reputation had been restored for making good programmes and getting the ratings. I still think when he went, Grade should have been given the job.